「マレートラと人間におけるコロナウイルス2019感染症の集団発生 ―― アメリカ合衆国テネシー州、2020年の事例」 『新興感染症』 2022年4月 28巻4号

2022 Mar 12; 28 (4). doi: 10.3201/eid2804.212219., Heather N Grome, Becky Meyer, Erin Read et al., SARS-CoV-2 Outbreak among Malayan Tigers and Humans, Tennessee, USA, 2020, Volume 28, Number 4 — April 2022

Heather N. GromeComments to Author , Becky Meyer, Erin Read, Martha Buchanan, Andrew Cushing, Kaitlin Sawatzki, Kara J. Levinson, Linda S. Thomas, Zachary Perry, Anna Uehara, Ying Tao, Krista Queen, Suxiang Tong, Ria Ghai, Mary-Margaret Fill, Timothy F. Jones, William Schaffner, and John Dunn

『新興感染症』(Emerging Infectious Diseases)はアメリカ疾病予防管理センター(Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC)が発行する雑誌で、本論文は同誌の2022年4月 28巻4号に掲載されたものである。本論文はテネシー州の動物園でマレートラに発生したコロナウイルス2019アルファ株(SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7)の集団感染を報告している。

広川による和訳を付して、以下に本文を示す。なお筆者(広川)の訳はこなれた日本語で分かりやすく記述することを重視したため、必ずしも逐語訳にはなっていない。文意を通じやすくするために補った語は、ブラケット [ ] で囲った。

| SARS-CoV-2 Outbreak among Malayan Tigers and Humans, Tennessee, USA, 2020 | |||

| (「マレートラと人間におけるコロナウイルス2019感染症の集団発生 ―― アメリカ合衆国テネシー州、2020年の事例) | |||

| In October 2020, the Tennessee Department of Health (Nashville, Tennessee, USA) was notified of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in 3 Malayan tigers (Panthera tigris jacksoni) at a zoo in the state. Felids, including domestic cats and exotic big cats, have greater susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection than other species (1–4). Infected domestic cats can transmit the virus to other cats via respiratory droplets or direct contact (4–6). However, the risk for cat-to-human transmission remains unclear. We investigated the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in Tennessee to determine its source and provide recommendations to control the spread of infection. | 2020年10月、テネシー州の動物園で三頭のマレートラ(Panthera tigris jacksoni)がコロナウイルス2019感染症に罹ったとの知らせが、同州保健局(テネシー州ナッシュヴィル)にもたらされた。イエネコと外国産大型ネコを含むネコ科動物は、他の動物種と比較して、コロナウイルス2019に感染しやすい(1–4)。イエネコが感染すると、呼気中の体液または直接的接触により、他のネコにウイルスをうつす(4–6)。しかしながらネコからヒトにうつる危険性については未だ明らかになっていない。我々はテネシー州におけるコロナウイルス2019の集団感染を調査し、感染源を特定するとともに、感染拡大を阻止するにはどうすべきかを考察した。 | ||

| The Study | 研究 | ||

| Tiger 1, the index case, began showing clinical signs of coronavirus

disease (COVID-19), including lethargy, anorexia, and nonproductive cough,

on October 12, 2020. Subsequent onset of clinical signs occurred in tiger

2 on October 16 and in tiger 3 on October 17. Oropharyngeal swab specimens

were collected under sedation on October 19 and October 27 for SARS-CoV-2

diagnostic testing and submitted to the Runstadler Laboratory, Cummings

School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University (North Grafton, Massachusetts,

USA) for initial testing for open reading frame (ORF) 1b-nsp14 (7). Presumptive

positive SARS-CoV-2 diagnoses were made in all 3 animals by real-time reverse

transcription PCR (RT-PCR) performed by using Mag-Bind Viral RNA Xpress

Kit (Omega BioTek, https://www.omegabiotek.com) and UltraPlex 1-Step ToughMix (Quantabio, https://www.quantabio.com). Tiger specimens were then sent to the US Department of Agriculture National Veterinary Services Laboratories (Ames, Iowa, USA) for confirmation by RT-PCR and whole-genome sequencing (3). |

2020年10月12日、倦怠感、食欲不振、乾性の咳(希望分泌液を伴わない咳)をはじめとするコロナウイルス2019感染症の症状がトラ1に現われ、10月16日にはトラ2に、10月17日にはトラ3に、臨床徴候が現われた。10月19日及び10月27日にはコロナウイルス2019の診断を目的とし、口腔咽頭拭い液が鎮静下で採取され、開放読み枠(ORF)1b-nsp14を初期検査で検出するために、タフツ大学獣医学部カミングズ校ランスタドラー研究所(マサチューセッツ州ノース・グラフトン)に送られた(7)。オメガ・バイオテック社のマグ=バインド・ウイルスRNA迅速キット、ならびにクアンタバイオ社のウルトラプレックス・ワンステップ・タフミックス検査キットを使用して即時逆転写PCR(RT-PCR)を行ったところ、三頭すべてにコロナウイルス2019の予備的陽性判定が出た。次にトラの検体はアメリカ合衆国農務省の国立獣医学研究所(アイオワ州エイムズ)に送られ、逆転写PCRと全ゲノム配列の解読が行われた。 | ||

| We conducted an environmental assessment at the zoo on October 29,

2020. The tiger exhibit has 3 primary outdoor visitor viewing areas: 2

outdoor viewing areas with fencing between humans and animals creating

a separation of ≈6 feet, and 1 outdoor overhead viewpoint where visitors

could view animals from a platform ≥8 feet above the tiger enclosure.

The tiger's off-exhibit den areas have concrete walls between each animal

enclosure and metal interior caging with open airflow that enables keepers

to see the tigers. The den areas are directly adjacent to or across from

each other. |

我々は2020年10月29日に当該動物園において環境評価を実施した。トラの展示には三つの主要な野外観覧エリアがある。うち二つの野外観覧エリアはヒトとトラの間に仕切りがあり、両者はおよそ

6フィート(1.8メートル)離れている。もう一つの野外観覧エリアは上部に設置されており、8フィート(2.4メートル)以上の高さに設けられた場所からトラの囲いを覗き込むようになっている。トラの寝室は観客から見えない所にあって、各個体の囲いはコンクリートの塀で仕切られている。飼育員とトラの間は金属の柵になっていて空気の流れは遮られず、飼育員からトラの様子が見えるようになっている。各個体の寝室は互いに隣り合っているか、または飼育員用通路を挟んで向かい合っている。 |

||

| We observed consistent use of personal protective equipment by zoo employees and veterinary students according to zoo policy. All employees and students in close contact with the tigers before the animals began to show signs of illness wore disposable gloves and cloth facemasks. After the onset of clinical signs of illness and SARS-CoV-2 testing in tigers, persons in the tiger den area wore protective coveralls, disposable gloves, and plastic face shields. At the time of this outbreak in October 2020, fewer data existed for relative mask efficacy, and mask types were not further specified by zoo policy. | 当該動物園の職員と獣医学生は、動物園の就業規則に従い、常に防護用の装備を身に着けていた。病気の徴候を見せ始める前のトラに濃厚接触のあった職員と獣医学生は、全員が使い捨ての手袋と布製マスクを着用していた。トラに病気の臨床徴候が現われてコロナウイルス2019の検査が実施されて以降、トラの寝室に入る者は全身防護衣、使い捨て手袋、プラスチック製ファイス・シールドを着用した。2020年10月にこの集団発生が起きた時点で、マスク着用の効果に関するデータは現在ほど揃っておらず、動物園の就業規則にもマスクのタイプは指定されていなかった。 | ||

| Before and after onset of animal illness, cleaning practices in the off-exhibit cages included use of high-pressure water hoses to clean the floors. Staff used disinfectants daily in the den area, and we confirmed disinfectants were on the US Environmental Protection Agency's List N: Disinfectants for Coronavirus (COVID-19) (https://www.epa.gov/coronavirus/about-list-n-disinfectants-coronavirus-covid-19-0). All zoo employees and veterinary students used a self-reported evaluation tool via mobile phone that screened for COVID-19 symptoms before their shifts. Zoo visitors were encouraged to wear masks; masks were not required in outdoor spaces at the time of this outbreak. | 観客の目に触れない寝室の清掃は、ホースから高圧の水を出して床を洗い流していた。この方法はトラが発症する以前から行われ、発症以後も変わっていない。職員は寝室を毎日消毒しており、使用されているのはコロナウイルス2019用消毒剤としてアメリカ合衆国環境保護局のN表に記載があるものであった。動物園の職員と獣医学生は、自分のシフトに入る前に、コロナウイルス2019感染症の症状が出ていないかどうか、自己診断による申告を携帯電話で必ず行っていた。動物園の客はマスク着用を求められていたが、今回の集団感染発生時に、戸外のマスク着用は義務付けられていなかった。 | ||

| We also conducted an epidemiologic investigation on October 29, 2020. Our investigation focused on the timeframe beginning 2 weeks before onset of index tiger clinical signs (starting September 28) until date of investigation (October 29). We identified 18 zoo employees and veterinary students who prepared food for or were in close contact with the tigers during this timeframe. For this investigation, we defined close contact to tigers as being within 6 feet of any tiger at the zoo for any length of time during the observation period (September 28–October 29). We selected these proximity criteria based on the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) definition of close contact defined (8); however, SARS-CoV-2 transmission can occur from inhalation of virus in the air >6 feet from an infectious source (9, 10). During the week after the index tiger showed signs of illness, community transmission of SARS-CoV-2 was at a 7-day average of 101 new cases/day in the county where this zoo is located, and the 7-day test positivity rate was 10.2%. | 2020年10月29日には疫学調査も実施した。指標となるトラ(最初のトラ)が諸徴候を示し始めた日を二週間遡る9月28日から、疫学調査を始めた10月29日の間に焦点を当てて調べたところ、この期間にトラの食餌を調えたり、トラと濃厚接触があったりした職員及び獣医学生は十八名が見つかった。本調査に際して、観察期間内(9月28日から10月29日まで)に、いずれかのトラから 6フィート(1.8メートル)以内に近づいていれば、時間の長さを問わず濃厚接触とみなした。6フィート以内という距離を選ぶにあたっては、アメリカ疾病予防管理センター(CDC)による濃厚接触の定義(8)に準じた。しかしながら感染源から 6フィートを超える隔たりがあっても、呼吸の際にウイルスを吸い込めば、コロナウイルス2019への感染は成立しうる(9, 10)。動物園が所在する郡において、最初のトラが病徴を示し始めた翌週のコロナウイルス2019新規感染者数は、一日平均 101人であった。また同じ7日間に同郡でコロナウイルス2019の検査を受けた人が陽性と判定される確率は、10.2パーセントであった。 | ||

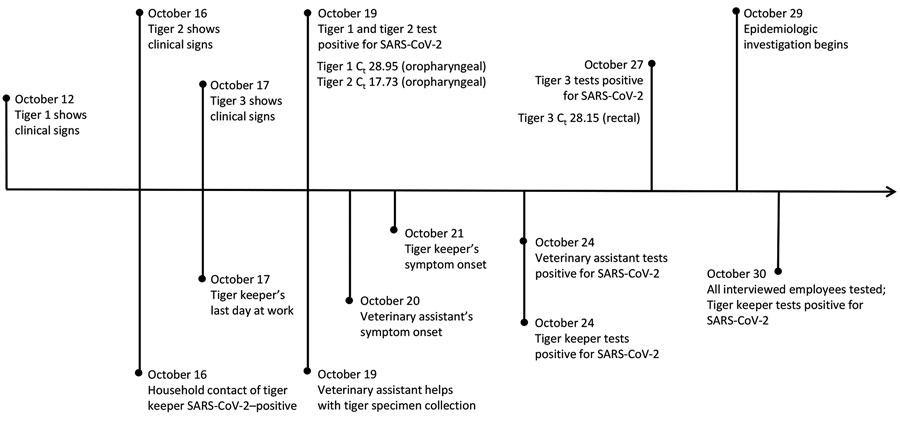

| We identified 2 employees with COVID-19 during the September 28–October 29 timeframe: a tiger keeper and veterinary clinic assistant. Contact tracing identified an additional household contact to the SARS-CoV-2–positive tiger keeper, but no other SARS-CoV-2–positive contacts were identified. We created a timeline comparing signs of animal illness onset and RT-PCR cycle threshold values with dates of zoo employee symptom onset and testing (Figure 1). | 9月28日から10月29日の間にコロナウイルス2019感染症になった職員は、二人であった。一人はトラの飼育員で、もう一人は動物病院の助手である。トラの飼育員と動物園外で接触していたコロナウイルス2019の陽性者一名が判明したが、[トラの周辺では]他にコロナウイルス2019の陽性者はいなかった。トラの病徴出現と逆転写PCRのサイクル閾値を、動物園職員の病徴出現及び検査[の日付]と[並べて]、時系列の図を作成した(図1)。 | ||

|

|||

| Figure 1. Timeline of events identified during the epidemiologic investigation of an outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 infection among Malayan tigers and humans at a zoo, Tennessee, USA, October 12–30, 2020. Dates related to tiger events are shown above the timeline; dates related to human events are shown below the timeline. Ct values for the first positive open reading frame 1b reverse transcription PCR test per animal are shown; methods for extraction and Ct value calculation were described previously by Sawatzki et al. (11). | 図1 2020年12月12日から30日の間に、アメリカ合衆国テネシー州の動物園で、マレートラとヒトにコロナウイルス2019の集団感染が発生した。疫学調査の際に判明した事象を、時系列で表す。時間軸よりも上はトラに関する事象、下は人に関する事象である。最初の陽性判定は開放読み枠 1bで得られたが、その際に行われた逆転写PCR検査のサイクル閾値はトラの個体ごとに示されている。検体の抽出方法とサイクル閾値の算出方法はサワツキらの論文(11)が先に示した通りである。 | ||

| Ct, cycle threshold; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. | 図中の Ctはサイクル閾値(cycle threshold)、SARS-CoV-2はコロナウイルス2019(severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2)を示す。 | ||

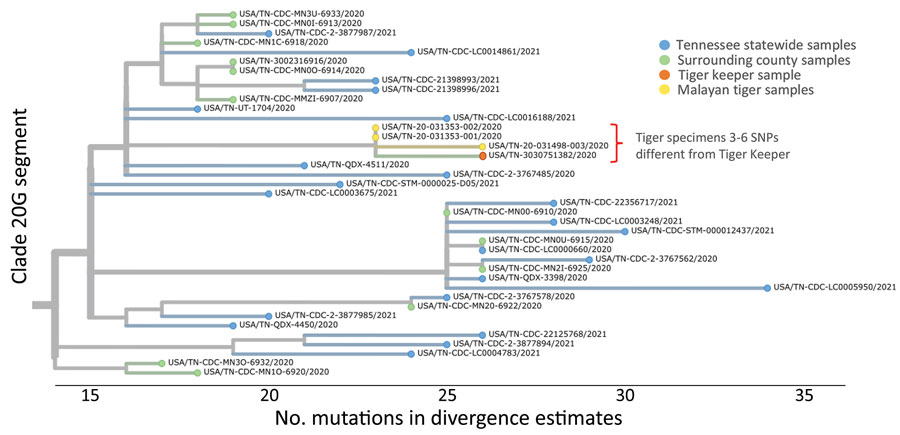

| We sent specimens from all zoo employees and veterinary students who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 to CDC for sequencing and genomic analyses. CDC staff performed whole-genome sequencing as previously described (12). We phylogenetically compared tiger sequences with 30 sequences from geographically-associated human SARS-CoV-2 cases collected from the county surrounding the zoo during October 29–November 12, 2020. We also compared tiger sequences with 233 statewide background sequences from specimens collected in Tennessee during March 1–November 12, 2020. | 我々は動物園でコロナウイルス2019陽性になった全職員及び全獣医学生から検体を提出してもらい、ゲノム配列の読み取りと分析のためにアメリカ疾病予防管理センター(CDC)に送付した。CDCの職員は別稿に示した方法で全ゲノム配列の読み取りを行った(12)。我々はトラから得られた検体のゲノム配列を、地理的に結びつきのあるヒトから得られた30種類のゲノム配列と比較して、ウイルスの系統関係を調べた。ヒトのウイルス検体は2020年10月29日から11月12日の間に、動物園が所在する郡において、コロナウイルス2019陽性者から集められたものである。さらに我々はトラのウイルスのゲノム配列を、州全体で得られた233例のゲノム配列と比較した。233例のウイルスのゲノムは、2020年3月1日から11月12日の間に、テネシー州で集めた検体から得られたものである。 | ||

| Most viral sequences clustered into NextStrain Clade 20G and Pangolin lineage B.1.2, which correspond to the predominant clades observed for human specimens from Tennessee during the time of the outbreak at the zoo. Nucleotide sequence analysis of viral sequences from the tigers (GISAID accession nos. EPI_ISL_2928444–6; https://www.gisaid.org) and the tiger keeper (GenBank accession no. OK170070) also clustered in SARS-CoV-2 clade 20G by Nextstrain tree (Figure 2). | [トラの]ウイルスから得られたゲノムは、おおむねネクストストレインのクレード20G及びパンゴ系統B.1.2に集中した。これらのクレードは動物園で集団感染が起こっていたあいだ、テネシー州内で感染したヒトにおいて支配的であったクレードと一致している。トラのウイルスから得られたヌクレオチドのゲノム配列(ジゼイドの受け入れ番号 EPI_ISL_2928444–6; https://www.gisaid.org)、及びトラの飼育員のウイルスから得られたヌクレオチドのゲノム配列(ジェンバンク受け入れ番号 OK170070)に関しても、コロナウイルス2019のネクストレイン系統樹でいえばクレード 20Gに収束することがわかった(図2)。 | ||

| The multiple alignment of 4 SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences (tigers 1, 2, and 3 and the tiger keeper) showed a total of 6 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) across 4 genomes. Sequences from tigers 1 and 2 were identical and had no substitutions compared with the reference sequence at those 6 SNP positions. Tiger 3's SARS-CoV-2 sequence contained 3 substitutions that were nonsynonymous G12565T (ORF1a: Q4100H), C17822T (ORF1b: P1452L), and G19889A (ORF1b: R2141K), and the tiger keeper's SARS-CoV-2 genome sequence had 3 synonymous substitutions (C1498T, C24904T, T26048C) compared with tigers 1 and 2. SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences from the tiger keeper and tiger 3 had 6 SNP differences. Genomic and epidemiologic data suggest that tiger-to-tiger transmission occurred under natural conditions, and genetic change occurred in vivo for tiger 3's sequence. | トラ1、トラ2、トラ3、トラの飼育員のコロナウイルス2019から得られた四組のゲノム配列は系統樹上で数本の分岐に亙るが、これら四組のゲノムは合計 6箇所の一塩基多型を示していた。トラ1、トラ2に由来するウイルスのゲノム配列は完全に同一であり、一塩基多型が生じている上述の6か所に関して、比較元のゲノム配列と比較しても、[異なる塩基への]置換は起こっていなかった。トラ3に由来するコロナウイルス2019のゲノム配列は三か所に置換があり、それらはトラ1、トラ2と非同義の G12565T (開放読み枠1a: Q4100H), C17822T (開放読み枠1b: P1452L), G19889A (開放読み枠1b: R2141K) であった。トラの飼育員に由来するコロナウイルス2019のゲノム配列は3か所に置換があり、それらはトラ1、トラ2と同義の C1498T, C24904T, T26048C であった。トラ飼育員とトラ3に由来するコロナウイルス2019のゲノム配列には、6か所の置換があったことになる。トラからトラへのウイルス伝達は自然の状況下で起こり、トラ3においてはその体内でウイルスの遺伝子が変異してかかるゲノム配列となったことが、ゲノムのデータ及び疫学的データから示唆されている。 | ||

|

|||

| Figure 2. Whole-genome phylogenetic analysis of an outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 infection among Malayan tigers and humans at a zoo, Tennessee, USA, October 2020. The tree shows a close-up view of clade 20G divergence estimates from the SARS-CoV-2 Wuhan-Hu-1 reference genome and sequences from humans living in Tennessee and Malayan tigers sampled during the outbreak investigation. | 図2 2020年10月にテネシー州の動物園でマレートラとヒトに発生したコロナウイルス2019感染症の集団感染に際し、ウイルスの全ゲノムを分析した系統樹。ここに示す樹形は、武漢型コロナウイルス2019(Wuhan-Hu-1)から分岐したゲノムの系統関係を推定し、このうちクレード20Gの部分を拡大表示したものである。集団発生の調査が行われている期間内にテネシー州に居住するヒトとマレートラから得られたコロナウイルス2019のゲノム配列は、いずれもクレード20に属する。 | ||

| Sequence analysis showed 3–6 SNP differences between 1 human tiger keeper and all 3 tiger sequences (GISAID accession nos. EPI_ISL_292844–6). Differences are indicated by 1-step edges (lines) between colored dots (individual SARS-CoV-2 sequenced infections). Numbers indicate unique sequences. | トラの飼育員であるヒトのウイルスと、トラ三頭のウイルスのゲノム配列(ジゼイドの受け入れ番号 EPI_ISL_292844 から 2928446)を分析すると、3か所ないし6か所に一塩基多性が見つかった。色付きのドットは、ゲノム配列が解読された個々のコロナウイルス2019を表す。ゲノム配列に違いがある場合、色付きのドットに至る線を並行に分岐させて示している。個々のゲノム配列ごとに数字が割り振られている。 | ||

| Phylogenetic relationships were inferred through approximate maximum-likelihood analyses implemented in TreeTime (13) by using the NextStrain pipeline (14). All high-quality genome sequences from Tennessee were downloaded from the GISAID (https://www.gisaid.org) database on March 16, 2021. Pangolin lineages for investigation sequences were assigned on March 16, 2021. Not all analyzed sequences are shown in this figure because some were outside clade 20G. | 点突然変異同士の系統発生的関係は、ネクストストレインの解析パイプライン(14)を使用し、ツリーラインで実行された分析(13)において、蓋然性が最も高いとされた推論による。テネシー州で採取されたウイルスゲノム配列に関する質の高いデータは、いずれも 2021年3月16日にジゼイド(https://www.gisaid.org)のデータベースからダウンロードされたものである。本論文で調査対象となったゲノム配列のパンゴ系統名は、2021年3月16日に割り当てられた。今回の調査で分析したゲノム配列がクレード20に属さない場合、本図には掲載していない。 | ||

| CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism. | 図中のCDCはアメリカ疾病予防管理センター(Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)を表す。SARS-CoV-2はコロナウイルス2019(severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2)を表す。SNPは一塩基多性(single-nucleotide polymorphism)を表す。 | ||

| Conclusions | 結論 | ||

| We describe SARS-CoV-2 infection in captive tigers with respiratory

clinical signs and provide additional evidence for nonhuman species as

hosts for SARS-CoV-2. Findings of this study support tigers' susceptibility

to the virus and potential for sustained transmission among large cats

and a risk for zoonotic transmission to humans. |

本研究は動物園のトラがコロナウイルス2019に感染して呼吸器系臨床徴候を示した事例を扱い、ヒト以外の動物がこのウイルスの宿主となる例を[既存の事例に]加えている。トラはコロナウイルス2019に感受性を有し、大型ネコの間でコロナウイルス2019は持続的に伝播する可能性があり、人に対しても動物由来の感染が起こりうる。本研究で得られた知見は、これらの裏付けとなっている。 | ||

| The SARS-CoV-2 sequence from the tiger keeper was 3 SNPs different from tigers 1 and 2 and 6 SNPs different from tiger 3. The close genetic relationship between viruses of the tigers and tiger keeper is consistent with the timing of clinical signs of illness and job duties of the tiger keeper, although transmission source or zoonotic transmission cannot be proven from these data alone. | トラの飼育員から採取されたコロナウイルス2019のゲノム配列は、トラ1及びトラ2と比較した場合、3か所で一塩基多性を有していた。またトラ3と比較した場合、6か所で一塩基多性を有していた。三頭のトラに由来するウイルスと、トラの飼育員に由来するウイルスの間には密接な遺伝学的関係があり、このことは病気の臨床徴候が出現した時期及びトラ飼育員の勤務日と符合する。ただし最初の感染がトラ及びヒトの誰から始まったのか、トラからヒトへの感染が起こったのかを、これらのデータのみに基づいて明らかにすることはできない。 | ||

| These findings have implications for both the public health and zoologic communities. Zoos should be aware of the possibility of animal infection through incidental exposure by the public or asymptomatic staff members. Humans with known or suspected infection should avoid direct or indirect exposure to susceptible species unless completely unavoidable to avoid potential transmission. Results of this investigation should also prompt zoo and wildlife organizations to reevaluate biosecurity and administrative protocols to minimize risk to and from employees, students, volunteers, and the visiting public interacting with susceptible species. | 本研究で得られた知見は、公衆衛生関係者にとっても動物学分野の関係者にとっても意味を有する。動物園の動物は観客や無症状の職員への偶然的曝露によって感染しうるのであり、動物園はこのことを念頭に置くべきである。職員の感染が判明し、あるいは感染が疑われる場合には、動物への伝染を避けるために、不可避の場合を除いて、直積的であれ間接的であれ、病原体に感受性を有する動物との接触を避けるべきである。職員、研究員、ボランティア要員、観客が病原体に感受性を有する動物とかかわる際には、病気をうつしたりうつされたりしてはならない。我々の研究結果が示す通り、動物園関連団体及び野生動物関連団体は、感染症対策と運営規則を見直すべきである。 | ||

| Dr. Grome is an infectious diseases physician and Epidemic Intelligence Service officer in the Center For Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia. She is currently assigned to the Tennessee Department of Health in Nashville, Tennessee. Her research interests include communicable disease prevention for vulnerable populations. | グローム博士は感染症を専門とする内科医であり、アメリカ疾病予防管理センター(ジョージア州アトランタ)の監視・疫学・実験センターにおける伝染病情報サービス担当者でもある。現在の所属はテネシー州健康局(テネシー州ナッシュヴィル)である。グローム博士が専門とする研究分野には、伝染病に罹り易い層の罹患予防が含まれる。 | ||

| Acknowledgments | 謝辞 | ||

| This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant

no. HHSN272201400008C/AI/NIAID to K.S.) |

我々はアメリカ国立衛生研究所から研究費を支給された。K.S.への研究費支給番号 HHSN272201400008C/AI/NIAID |

||

References

| 1. | Bosco-Lauth AM, Hartwig AE, Porter SM, Gordy PW, Nehring M, Byas AD, et al. Experimental infection of domestic dogs and cats with SARS-CoV-2: Pathogenesis, transmission, and response to reexposure in cats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:26382–8. | ||

| 2. | Bao L, Song Z, Xue J, Gao H, Liu J, Wang J, et al. Susceptibility and attenuated transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 in domestic cats. J Infect Dis. 2021;223:1313–21 | ||

| 3. | McAloose D, Laverack M, Wang L, Killian ML, Caserta LC, Yuan F, et al. From people to Panthera: natural SARS-CoV-2 infection in tigers and lions at the Bronx Zoo. MBio. 2020;11:e02220–20. | ||

| 4. | Shi J, Wen Z, Zhong G, Yang H, Wang C, Huang B, et al. Susceptibility of ferrets, cats, dogs, and other domesticated animals to SARS-coronavirus 2. Science. 2020; 368:1016–20. | ||

| 5. | Halfmann PJ, Hatta M, Chiba S, Maemura T, Fan S, Takeda M, et al. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in domestic cats. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:592–4. | ||

| 6. | Barrs VR, Peiris M, Tam KWS, Law PYT, Brackman CJ, To EMW, et al. SARS-CoV-2 in quarantined domestic cats from COVID-19 households or close contacts, Hong Kong, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:3071–4. | ||

| 7. | Cushing AC, Sawatzki K, Grome HN, Puryear WB, Kelly N, Runstadler J. DURATION OF ANTIGEN SHEDDING AND DEVELOPMENT OF ANTIBODY TITERS IN MALAYAN TIGERS (PANTHERA TIGRIS JACKSONI) NATURALLY INFECTED WITH SARS-CoV-2. J Zoo Wildl Med. 2021;52:1224–8. | ||

| 8. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Case investigation & contact tracing guidance 2021 [cited 2021 September 30]. | ||

| 9. | Cai J, Sun W, Huang J, Gamber M, Wu J, He G. Indirect virus transmission in cluster of COVID-19 cases, Wenzhou, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1343–5. | ||

| 10. | Jang S, Han SH, Rhee JY. Cluster of coronavirus disease associated with fitness dance classes, South Korea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1917–20. | ||

| 11. | Sawatzki K, Hill NJ, Puryear WB, Foss AD, Stone JJ, Runstadler JA. Host barriers to SARS-CoV-2 demonstrated by ferrets in a high-exposure domestic setting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118:e2025601118. | ||

| 12. | Paden CR, Tao Y, Queen K, Zhang J, Li Y, Uehara A, et al. Rapid, sensitive, full-genome sequencing of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:2401–5. | ||

| 13. | Sagulenko P, Puller V, Neher RA. TreeTime: Maximum-likelihood phylodynamic analysis. Virus Evol. 2018;4:vex042. | ||

| 14. | Hadfield J, Megill C, Bell SM, Huddleston J, Potter B, Callender C, et al. Nextstrain: real-time tracking of pathogen evolution. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:4121–3. |

Figures

Article Citations

Highlight and copy the desired format.

| EID | Grome HN, Meyer B, Read E, Buchanan M, Cushing A, Sawatzki K, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Outbreak among Malayan Tigers and Humans, Tennessee, USA, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022;28(4):833-836. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2804.212219 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| AMA | Grome HN, Meyer B, Read E, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Outbreak among Malayan Tigers and Humans, Tennessee, USA, 2020. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2022;28(4):833-836. doi:10.3201/eid2804.212219. | ||

| APA | Grome, H. N., Meyer, B., Read, E., Buchanan, M., Cushing, A., Sawatzki, K....Dunn, J. (2022). SARS-CoV-2 Outbreak among Malayan Tigers and Humans, Tennessee, USA, 2020, Emerging Infectious Diseases, 28(4), 833-836. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2804.212219. |

DOI: 10.3201/eid2804.212219

Table of Contents – Volume 28, Number 4—April 2022

アカデミア神戸 医療関係資料 インデックスに戻る

アカデミア神戸 大人のための教養講座 インデックスに移動する

アカデミア神戸 トップページに移動する

Ἀναστασία ἡ Οὐτοπία τῶν αἰλούρων ANASTASIA KOBENSIS, ANTIQUARUM RERUM LOCUS NON INVENIENDUS